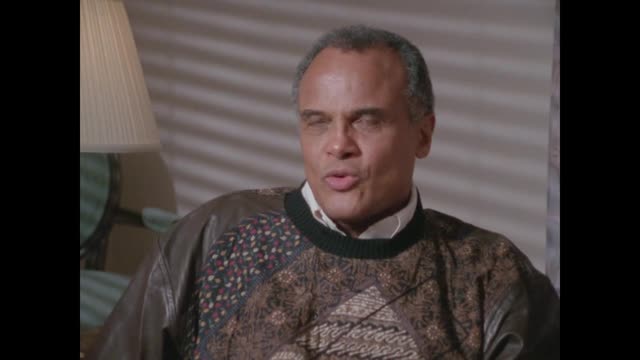

Eyes on the Prize II; Interview with Harry Belafonte

- Transcript

One last thing that is if you can use my question in your answer, so that if I ask you about my power, just, hey, can you have a, we're rolling. Do you have a first memory of the concept of words, black power? What it first arrived on the scene in its foreblown infancy, so to speak, by that I mean there always been a quest for power. The whole struggle in the civil rights movement was a constant reflection of a certain amount of powerlessness that it permeated through black life, black culture, black aspiration.

So I think people were constantly in touch with the idea that we were in need of power. And Dr. King's position on the movement in its broadest sense and seeing it as all encompassing, not just for black needs, but for the needs of all of those who reflected in existence in the underclass or in the poor peoples of our country. Dr. King was somewhat careful in how he used racial definitions to characterize aspects of the movement. So no one ever really talked to the idea of black power as such.

It carried with it a host of definitions that for many was an unsafe, certainly that was the response of many people when we first heard it. But when it arrived, and when it was used as effectively and as powerfully, as rap brown used, it is stokely used, it is all of the guys out of SNCC and the women out of SNCC applied it. It touched something that was irreversible. Those who were afraid of it because it suggested anger and it suggested aggression were justified in that as one of its definitions. Because it did represent a certain kind of aggression.

It represented a certain kind of psychological aggression. It meant that we were seizing a position that a goal was very clearly defined, black power. All that we were to do from this day forward was going to be something that infused the idea that black people would no longer be powerless. That whatever we may have achieved, even if we achieved civil rights from the SNCC perspective, and I think with great validity, also from Dr. King's incidentally. But even if you had achieved civil rights, one did not necessarily achieve power as we have come to understand. I just take a sip of water, take a sip of water, that's going to play you all alone. That's the nature of the beast.

Can I get you to think about your particular character between camps in many ways, between Stoke Lake or Michael and Rapp and the SNCC kids at Dr. King's at CLC? Do you remember being in that role? Oh yes, very clearly it was a role that had been... Island given the role. It was a very difficult role to be in, but it was also a great challenge in a way. People in SNCC, I think, trusted me a great deal because from the very beginning of the formation of SNCC, I had been very supportive of it and continued to be all through its existence. And I had been one of the primary sponsors financially of SNCC. I had a number of meetings with SNCC in its earliest formation.

The Council of Ella Baker and things that I had discussed with her gave me a great deal of insight into what SNCC was about and what SNCC had hoped to achieve. And I felt very comfortable with that. I felt that their suspicion and their sensitivity to SCLC and the elders of the Black community who represented it, that that was historical and it was classic and it was the way it should have been. Young people are always in rebellion against the elders and the leaders. If you come upon a moment in history when that history is not moving forward in some positive and some meaningful way, and certainly Black people in this country were deeply frustrated by what had happened to and was happening to existing Black leadership, Roy Wilkins, Whitney Young, even leaders prior to that.

The great and the vibrant leaders, Paul Robeson and the boys had all had been contained. There was really no aggressive voice doing for us what youth felt should be done. So I was very satisfied that SNCC served a very important dimension to the movement. They were going to become the provocateurs, they were going to become the radical voice, they were going to become the voice of non-compromise, which I felt was vital to the movement. At that point in the position in the late 65s, 66s, about beginning to exclude whites from the movement. Yes. That was a position of great stress. It was a position of great stress because it was around a very specific individual when it erupted. It was around a young man by the name of Bob Zona, who was a white member of SNCC and had certainly evidenced his deep commitment to the struggle and his willingness to go wherever anyone else went in the quest for the end to racism.

He was not the only individual, but he was a primary force because he was certainly one of the most upfront of any of the whites who had been involved in SNCC. When the question arose, most people thought it was a decision that had been reached based upon racial factors and had been defined almost exclusively as such, which was not the case. The case was really in the beginning quite tactical. The question was, with the whites who were in SNCC, involving themselves directly in the black community of events, wasn't it more beneficial to the movement to have these very same white people who were quite astute by now and very sensitive to a host of issues and had learned a great deal out of the black aspects of the movement? Wouldn't it have been more beneficial for them to move into the white communities and to do organizing in the white community since,

obviously, blacks could not do that effectively. What the white communities needed was white leadership and what better leadership was there available for that than the leadership that came out of the civil rights movement in SNCC and in other aspects of the movement in SCLC as well. So that this rather meaningful, I think, and substantive discussion and criticism yielded the result that SNCC would purge itself, which was, I always thought, it was unfortunate that SNCC's position on this had not been more clearly described. Certainly, that was the way I understood it, because when I had to talk with and discuss these events with Dr. King, that was the position that I represented to him because when I spoke to Stokeley, when I spoke to Rap, when I spoke to others in SNCC, and speaking to Bob Zelner himself, Zelner felt, as he had expressed to me then,

that it was an important crossroads in the movement, and that he felt that SNCC's position was correct. You were not only between SNCC and SCLC, but you were also raising a lot of funds for SCLC, and during those years, that these positions of black power and no white didn't, couldn't have made that any easier. No, it didn't make it any easier, as a matter of fact, the black power issue did not make raising funds a large portion of which... We'll have to last a minute. Roll that. Roll that. It's working, please. Ten seconds? It's been having a roll all the time.

It's been good. We need to see this late. Okay. That's a different one. Thank you. Just a couple of things that I think, just for archival or for other reasons, black power also did something beyond just setting a new dimension for the movement to such. It did a lot to unify people who had a history of certain levels and grades dissatisfaction within their own tribal characteristics. Light skin blacks and feeling somewhat removed from black skin blacks and blacks who had some Indian in them feeling a little bit different from blacks who... All those variables which people were having a problem with, you know, black power kind of just gave everybody a single place to be. And black in the use of the word black, in the reality to the psyche, black is really black.

But the black power movement said black is really black and using that as the base. We accept the fact that all gradations of that color is acceptable under the term black. So it became very unifying. Light skin blacks didn't have to sit back any longer. I watched thousands of light skin black people struggle with their condition as opposed to black skin blacks. It was a weird kind of thing to see emerged. I'd always been aware of it. But I never saw it display itself quite the way it did when the word black power came up. And it was a unifying, it was a very strange unifying thing. Everybody had finally a word that they could feel some universality with. It was universal black.

It said it all. It didn't get into gradations. Everything else seemed to have had gradations. And it was also a word that came out of a realizable and a recognizable black source. Everybody can debate where did Negro come from. Everybody can debate where did color come from. Everybody can debate the use of a host of definitions to describe us. But black power came from a nitty-gritty place, a vibrant movement, aggressive people taking charge of their lives. So it had that aura around it. And it was terrifying for a lot of white folks, even for a lot of black folks. But it was also a healing for, I think, most. It served, I think, a very healthy dimension at that time in the movement. It made me healthy, but how do you raise money around something that's that assertive? The ability to continue to raise funds from the sources that have been traditionally giving to us.

It became much more difficult because the quest for black power put a language into the mix that made people who were white and supportive of our cause who saw it in non-racial terms begin to take a position that this became a little too sectarian, became a little bit too alienating. It was now specifically towards a goal that suggested non-integration. It was much too much into the Malcolm X-cam, it was moving too, it was going too radical. And no matter how much one tried to explain that away, even accepting some of those definitions as applicable, but it had to be placed in a much larger context to be understood. And therefore, it continued to command a moral and ethical giving by those same sources.

It was very hard. And consequently, it fell upon me to begin to look to sources of funding that the movement had never examined before. And that was what led me to do a whole special trip throughout Europe to identify specific countries and to identify specific governments and to identify specific leaders who were deeply sensitive to our cause, who was not be turned off by emergence of certain slogans or words or definitions. And that would feel the commitment to our movement. And I selected two places in which to do a sampling as to the success of that possibility for new resources, not just economic, but also moral and political support coming from from an outside place. The first was in France, a huge benefit that was given in Paris,

which at first had come under the auspices of the American Church. It was under the clergy and the American Church. And then when the State Department and the FBI got through doing its mischief on Dr. King and had intimidated the Americans in Paris, they withdrew and left us with a date and left us with time and left us with mobilization, but we were not all committed to it. And it was interesting because it wasn't as if we had gone to Paris with a broad cross-section of the movement. I mean, we weren't only with Dr. King and even in the face of that, the Church, the American Church, withdrew its support. But French allies had gotten, and I explained to them what had happened that we were in this rather difficult and precarious

position that the Church had withdrawn its support from Dr. King and from our presence there, under the guise that we were somehow, according to FBI records, we're doing mischief and we're communist movement. And this French community stepped in and the leading artists of France and the leading sports figures in France all came together at the Palais de Spau. And they saved the day, the event turned out to be hugely successful. We made all of the French press and the international press and we received large contributions and it set up our basis to be able to continue to do this. Our next stop after that was in Sweden, where we got the King of Sweden and we got to be our patron. We got the Prime Minister to be our chairman. We got the Bank of Sweden to be the receptacle for our fundraising and we got the post office of Sweden to be our conduit.

And we did a whole Scandinavian hookup where all of the Scandinavian countries focused on one event, which was to be the first of many. In a concert, it was given Dr. King spoke and about a week later after returning to the United States at a meeting at the Swedish embassy. They presented Dr. King with, I think it was $250,000 check as the first offering from our efforts. We were somewhat encouraged by all of this because it was not only a new source of revenue for us economically but it was also a new source of power of we were beginning to touch the conscience of and give legitimacy to people who wanted to support us in the outside that didn't know quite how to do it. You were also in Africa and playing that role between the SNK kids and second tour. That was the young people of SNK going to Africa was a different set of circumstance.

When Schwerner, Goodman and Cheney were discovered missing and presumed murdered before that information had become fully before it had been evident before all facts had fallen into place. I was called by Jim Foreman and Jim said, we were at the tail end of the summer, the three civil rights workers are missing. All the students are going to go back to campus. I believe that the people of the south here in Mississippi are going to feel are not going to be able to understand all of the facts that the program had come to an end and that all the students

were leaving to go back north. It may be assumed that all the students were leaving and going back north not because of the new school year but because the three civil rights workers were murdered and that would look as if this act of intimidation had successfully aborted the voter registration campaign and that if this became evident this was interpreted as a fact that it would then have its ramifications to the Ku Klux Klan and others wishing to do evil doing it all over the south and using murder as an important weapon to impede the movement. What was required was a huge sum of money to be put in place by those students who would volunteer to stay on past that semester and stay in the south and continue to work especially in the face of the missing civil rights workers

and that the decision had to be arrived at very swiftly because the passion was there and the students were going to vote on it very shortly. Oh, yes, okay, let's start the second round, that's it. We're shooting film and cutting up it. Are you going to hit it?

With this state of emergency I asked Jim how much did he how much money was required here and he said between 50 and $60,000 and I had only a matter of a few days in which to raise this money. You have to understand that if we're just that one event alone that required money it would not have been as difficult but you have to understand that we were busy supplying money to so many levels of the movement that was becoming more and more difficult to find sources to give. Much of our money had been tied up in bail that was just not being returned by the courts for people who were on bail. Much of it had been given to other mobilizations and so on.

Jim called for this amount of money after having raised the initial sum for the voter registration of the students to begin with. It was a difficult thing to do so I had to hook up with people in various parts of the country and I had to get individual because there was no way to mobilize a rally or a benefit that had to be gotten from individuals with the understanding that it was quite possible that the money would not come back unlike bail and other things. But I set for myself another goal and that was I had become sensitive to the fact that many of the people in SNCC were on a burnout. They had really been on the front line for so long doing so much and have been beaten and battered and intimidated and still held the line but they were beginning to make mistakes. Decisions were being arrived at in ways that didn't sit well

and that what became very clear to me was that they really needed hiatus, they needed to get away, they needed to just stop for a minute and just do something very natural, rest the body, put the mind to bed for a second and when I thought about all the places in which that could possibly be done for me to do it in Africa and to be able to take at their selection a group to Africa to just go to stretch out to become part of an African environment in the country that was noted for its political progress and for its ideas and where it was going. I then took this fundraising moment to raise additional funds that I then gave to SNCC and I said the 60,000 is for the voter registration needs and the additional 10,000 that I've gotten here is really for your

transportation to take people who are the most in need of it and I know it was a difficult decision to make but it had to be made to just go on Africa for two weeks or three weeks and just really cool out. Because it was all black it was a place to which many people had eluded, many people talked about it, many people talked about the emerging black leadership of Africa hoping that America would fall in place with the with the Jomal Kenyatas and the Tamam boys and the Kwame and Krumas and the second two rays and the Julius Norerees who were emerging and I felt that excuse me I felt that in the African environment removed from civil rights removed from certain aspects of white pressure as was understood and political pressures were understood that it would be a very different place that there would be a chance to get out of self and to interface with a place that most of them had never been before.

Yeah, I think the person who was most affected by the trip, first let me change that. I can't say he was most affected because effect is not always immediate, it can be very long range and for a lot it was long range but the person who immediately appeared to be the most affected was Fannie Lou Hamer because when we arrived in the Ghanaian government it put us up as their guests so everything was as a gift from the government and they were given the best places in which to live and fellow Africans were there just to serve and to help with the needs of the guests and Fannie Lou Hamer was in the middle of taking a bath over in her area right in the middle of taking a bath when Saka Ture without any protocol without saying anything drove up to meet

we weren't supposed to meet him till the next day officially at the reception but he was doing this evening thing and drove by and I had to go over to tell Fannie Lou Hamer that the president had arrived and it was the only time I could every member of Fannie Lou Hamer getting totally rattled. I mean she said what no no no no you all playing a joke no no you don't do this to me I'm having a bath and she went and it was wonderful too and then when she when she was when she understood that we were telling the truth that he had come she dressed and she came to the meeting and after the meeting secretary talked through an interpreter after the meeting Fannie Lou started to cry and she said that she didn't know quite what would happen to her from this experience because for so long black people have been trying to get to the president of the United States of America

where we were citizens and where we had rights and could never see him and here in Africa when we had an appointment on a certain day this president came to see her was was was was I don't know metaphorically or somehow symbolically it meant a great deal to her and I don't think anybody who was on that trip ever saw themselves in quite the same way again but it was an environment that did a lot for the people who went and then when everybody came back I think it was a well it was an appropriate thing to do. I mean to Malcolm X my very first memory of Malcolm X was a matter of fact in Harlem at a street rally that he was speaking of and I listened to him and I was instantly aware of the fact that this was no ordinary human being this was not

a street side polemic somebody was looking for recognition and had a scam he was running this was for real and I knew very little about the black Muslim movement I was aware of its existence but it didn't texturally do much I was too distracted and too preoccupied and I never really saw in it the significance that had emerged and you about Elijah Muhammad and you about all of that out of Chicago and but it was something that was quite confined it wasn't until Malcolm X that it began to have national and international ramifications and the more I listened to him the more I found myself in conflict because I had seen in his utterances not so much

pride of manhood quote unquote pride of race I saw in it something that tactically disturbed me as it did others and that was if you beat the drums of war loudly enough and you make all of the members of the tribe war ready if they begin to trust that sound what happens when the moment comes to apply it and you discover that you are incapable of effectively making the difference you thought you could make because violence and the design of violence would be quickly snuffed out it was it was it was very troublesome and it wasn't until extensive conversations with Dr.

King that I not only felt somewhat supported in my query but was also supported in the fact that Malcolm was deeply deeply significant and that he was also doing something else that the other aspects of the movement was not doing and did not do until black power came along Malcolm brought an instant sense of being potent he put impotency aside for a lot of us and that made people very heady it really did it was a wonderful euphoric feeling to all of a sudden

get up one day and say yeah I'm really tough I'm resilient I'm bad he articulated so much that was pent up in in millions of black voices and for a long time his greatest satisfaction tactically correct or not it was the fact that he was a great tonic for what people needed to hear and to have some relief from certainly for me the greatest couplet the greatest thing that could possibly have been brokered at that time would have been a holy alliance between Dr. King and Malcolm many of us worked for that tenaciously it would certainly have meant that both forces would have done a great deal of examination about their position to find a basis on which to be able to come

together that would not make them have to retreat from from from from a role that they had cast for themselves because in retreat one would have it suggests defeat it suggests one surrender something I would hope that such a brokering would come about where where it was not a surrendering of anything but an amalgamation of something that yielded something terribly new and beautiful and I think that was I hope that many of us had and in fact had felt that Malcolm's trip to Africa and then ultimately his trip to Mecca when he came back and said which I thought was very key and very fundamental when he said I have been to Mecca and there is no race he he used this trip to Mecca to point out that he had seen all of all his children and they were blue-eyed and white skinned and black and brown skin and they came in in all colorations

and that he was beginning to view the future in in in in another dimension was for us I think a moment of a credible joy because it meant that he saw himself in universal terms he saw himself in all people terms and that that was the first basis excuse me that that was the first basis for Dr. King and he to be able to to come together he didn't live much long after that that was about to ask when we lost him you remembered the assassination and very clearly the feelings the assassination was a tremendous sense of loss a great loss first of all leaders were hard to come by they weren't just growing up every day not to the statue of a Malcolm and not to the

statue of a king we had leaders who were able to work in in in specific areas and do very specific things all of the strategic terribly important as an effect in the long haul they have been the most important because they became the caretakers the leaders that were local and what but from a national and international perspective we didn't have many who had that platform or given that platform because media still controlled who was hurt and who was not heard and certainly Malcolm had that platform and had it quite vigorously and he and Dr. King coming together was the most wanted goal yeah right well as he's usually was I think most clearly excuse me as his eulogy was clearly a reflection that was felt by everyone it was not

his eloquence in his own poetry is always there but I think that the glory of Malcolm and what he was potentially not even what he had achieved not even what he had overcome in his own personal life but to go on was was was was was for many of us it's not fact it gave the movement from the point of view of positive powerful leadership a more horizontal frame everything in our leadership has been vertical cut off the head you get everything else and that certainly was true of much of America in that period whether it was Kennedy's or whether it was king or whether it was Malcolm and and the host of others Malcolm's death cost us the man but if you watch this history he is he is gross yes I think that I think that Malcolm left us a legacy that will

forever be a well that young people or people in general can go to because our struggle is still very much in many of its characteristics exactly as it was in the 60s and the 50s and the 40s and the 30s and the 20s and it has in in in in very profound and meaningful ways changed very little we have examples of success we have examples of of people who appear to have overcome and has taken advantage of the integrationist spirit and then something with their lives which are held forth as a barometer for the other 30 million black people in this country to use as their guide

and therefore if you pursue your interest the way these illustrators have done then you too will become part of the great fabric of America suggesting that anything that we wanted to be was totally within our province and that we controlled everything so if we were poor hungry on crack dope struck out homeless hungry not employed it was our doing and that if we were just aspire to what the others were achieving that had gained media representation that just do it the way they did it and you'll be okay is one of the greatest hoax is ever and Malcolm often denounced that he often found those who sat in the position of privilege were sometimes the greatest instruments of of the greatest obstruction the black aspiration because it confused it

muddles the mind I don't know what the black kids I know what black kids really do when they look and they see you know Michael Jordan and a few million dollars and they see Sydney Portier and they see Eddie Murphy and they see the successes that appear to be mine only for the taking without any real sense of of how totally out of step those successes are they're unreal they have no basis in reality 94 white folks you know the anordinate success that some some blacks are experiencing given the condition from which we have come take your back to 65 66 67 and rebellion riots which we're now beginning to sprinkle sprinkle the blast the headlines and change the movement because it's a northern

phenomenon you remember the Detroit right very well first time flames really came into into very visit it was it was it was it was an unbearable experience for those of us who had sought to pursue the guidelines set down by Dr. King guidelines we either ourselves accepted I don't think it was as the person for whom it was the most troublesome was Dr. King himself the thing that he had feared most that violence would erupt uh that it would become a a a major player in the course of of our history was very very troublesome and he he wretched over trying to find the miracle that would make the difference because he felt

he had failed he felt that no matter how much one would define for him that social and historical and environmental circumstances were very very much at play he so believed in his objectives that he also saw himself as the missionary for that objective as having to be all omnipotent on some level that he should somehow be much more touched with the ability to inspire so that people could understand more fully that he was that he would somehow be able to get over and the Detroit riots was the beginning of a whole series of events that took him on a on a special course one meeting that we had at my home he had come back from a meeting in in Newark he had met with the mambo baraka don't lose that

as had to be done on a number of of major campaigns whether it was the march on Washington or Birmingham or Selma Montgomery certainly or poor people's campaign Dr. King came to New York we would convene a number of people from media journalists opinion makers leaders and Dr. King used that time to be able to give a firsthand discussion and her first hand definition as to what the campaign was about what he hoped to achieve what was the reason behind it what were the tactics and what would be the various moves that would be unfolded in the event of certain encounters this did one thing

in particular it did a lot of things in general but one thing in particular was that it gave allies to the movement and even those who were prepared to ask objective journalistic questions an opportunity to hear from King directly what the campaign was about so that once we unleashed the campaign there would be to try to get Dr. King at that time and to try to get a clear pictures to what was going on was not the most ideal environment in which to do it so we always convened strategic people to hear what Dr. King had to say and to query the objectives on such an occasion before coming to the meeting in New York my home Dr. King had to meet with the group in Newark at a place called Newark which is where a mama baraka had had quoted himself and Dr. King came late and he gave his his apology for

lateness went on with the discussion as to the campaign because it was the poor people's campaign that he was on his way to to Memphis at the end of that meeting when everybody had left Dr. King was highly highly agitated and he was you could tell when he pays he had his shoes were off his tie was open he was walking up and down the living room and talking and Andy was there and Bernard Lee was there my wife myself and there's one of the person that I think was Stan 11's not too sure but Dr. King was the first time that I heard him say something that we quoted quite a bit later on and he said I really am very very concerned because he's looking at all the riots and all the aggression that was beginning to emerge and he said this integration movement

is beginning to unfold things that I had never quite envisioned and I wonder if we're not in fact integrating into a burning house and he then began to it was the first time that I had heard him utter anything that suggested that there was another dimension to this whole thing we were going to go we were all going to have to go someplace else that for him by the time the poor people's campaign came about and all this eruptions think the civil rights bill as we eventually got he knew was coming nobody quite knew in what form what all the details would have been but he knew that victory was in hand that the civil rights movement itself would have to give way to something much more profound economic rights that's why he began to talk about the poor people's campaign

he saw the amalgamation now coming moving away from just blacks and whites looking to integrate but bring people together in a much more fundamental way around issues that affected everybody regardless of race class of color or not class but of course race of color or ideology it was a chance to bring the Native American the chance to bring in Hispanics the chance to bring on levels that they felt directly in tune with and it was at this time that he raised the question about integrating into a burning house he didn't accept that that's where we were going but certainly the question was there very largely it was in this context that writing I think required Dr. King to begin to dimensionalize because on hindsight now at the time Dr. King came into being there were less than 300 black elected officials on all levels of electoral politics by this time in our history

in the in the in the threshold of the 21st century in the 1990s we were looking at somewhere around 6,000 no I was just making it I was thinking about how prophetic okay okay I was just going to say that he said that it isn't just enough to get black people elected just don't make reference 1990s itself okay okay let me just reword that then at the time of the the movement emerged there was less than 300 black elected officials on all levels of electoral politics Dr. King although he felt that blacks using the voting process the constitutional basis for involvement and therefore changing much about

our conditions in life was not going to be exclusively the only handle that we had on our destinies of people because he maintained that for many not just for a handful but for many blacks who would begin to evidence themselves in these new roles electoral politics that their clear class interests would override their racial interests that once they began to feel opportunity was they began to feel success was they began to feel personal power that they would begin to drift away from the very thing that gave them the platform to begin with they would begin to drift away from from from meaningful black interests that they'd become part of a whole new thrust that they'd become a disillusionment in ways and that the only hope for the movement in this country was for

a people's movement that would be vigilant that would be eternally in motion as long as there was a need for it that would then serve notice on on because if there were leaders getting into office and no movement then we would we just have retrogressed and he saw all of this in that period of the eruptions in the cities and the violence and the displaced because to satisfy the use of Chicago and Detroit and other places it wasn't just about the vote it was about opportunity economic opportunity and getting so Dr. King saw in those riots both the frustration and the difficulties that were inherent in it and in it he saw some resultant effects he saw him in Chicago when he was trying to get the city of Chicago to come to grips with issues frustrated very frustrated because for instance in Chicago a northern city which didn't have the classic

image of a southern city racist mayor declared racist segregationist he came into Chicago he had this little apartment that he lived right in the heart of the ghetto he lived in in the environment that he was representing and he talked to Mayor Daly and Mayor Daly was certainly symbolically a liberal force within the Democratic Party he certainly had been there in a great friend of Mehalia Jackson and could evidence hundreds of black people who were known to him by first name and whom he had given a lot of opportunity and privilege to so he was a tough one to get in line and Dr. King knew that he was taking on a new kind of adversary that it was no longer now the the stereotypic segregationist white person from the south in tradition it was now coming to

something far more insidious the institutionalized the well-honed benevolent racist the one who who who sought in benevolent ways to give privilege but would not use his power to change the system and to change the condition because it was not his political interests to do so it was a new onslaught as a matter of fact in Chicago in the state of Illinois particularly in Cicero and the next time he came back it was the worst single experience that Dr. King ever had he felt closest to death in Cicero than he had anywhere he never saw hate quite as in the dimensions anywhere in the south and all that he'd been through as he saw in Cicero in Illinois because he saw it among

what he considered to be informed white folk who should have been very different he ever talked about the other level of white folk the liberal who had supported him in the south he ever perceived him again to withdraw when he moved that was daily that was the daily crowd daily was very much supportive of Dr. King in the movement when it was in the south I remember all that we're going to camera on 9000-687 is up it's still that I mean Dr. King had a great basis for that suspicion because the absence of affluent blacks from support to the movement almost every left not just money

but just in terms of visible support using their platform wherever they may be to help sell the cause was very very difficult to acquire it up until now even there are a lot of people who have never fully committed themselves to what the movement was about and that that was a very sharp line for Dr. King to understand that blacks would really look at class interests above racial interests human interests and therefore play a classic role in a in a class war sure to the new groups begin to appear on the scene and one of them using the symbol from Lowns County the black panther emerges in Oakland California men who call themselves black panther do you remember that phenomenon frightened of it stunned by it the proving of it but black panthers

and that was going to grow into a national player in this sort of next phase the black panthers did in fact cause quite a tremor in the movement it wasn't used so much that it was a group called the black panthers and they appeared to be quote unquote very militant and we're going to go to we're prepared to bear arms and we're prepared to go down that wasn't the problem the problem really was that there was such an inordinate level of intelligence that made up all those young men and women who came together I mean they I mean eldritch cleaver and the book that he wrote you know saw a lot of ice and hampton and Bobby Seale's all of them I mean when these young men spoke they spoke in such rich with such rich vocabulary and such passion

and such a depth of commitment that doctor can't often said that were I able to co-op to those minds into my cause there is no question that victory would be swift and eternal as events unfolded and as the black panthers used themselves to show the cutting edge of violence particularly in the north and the insidiousness of police and investigations and FBI they became a living instrument through which all these unholy alliances of those institutions locking together to serve notice on black people they were they were they were catalyst to hone you a set of information and certainly when the with the murder of hampton and all of that yielded in terms of information

certainly when the guys in Oakland had to come out undressed to show that they were not sort of in the event they were killed that they were not bearing any arms and that they were you know all those things at the black panthers devised in ways to to show the corruption and the oppressiveness of the system became very meaningful and became very real and became very tangible and best expressed I think in in in the court trials of the Chicago 7 in which the black panthers were represented. You were you were very close to Dr. King the awareness of people surveilling, watching and listening and other faces of the movement was it something you ever talked about? Talked about constantly. It was the awareness that it existed

it would have been silly to assume that it didn't exist number one so first of all there is no way for the federal view of investigation to have conducted its affairs the way it conducted its affairs if it was not specifically hostile to us and to the movement and everything it represented and that for J. Edgar Hoover to find some moral basis on which he would contain himself from doing the evil that he did was just not there was no way that equation didn't exist he was too corrupt he was too evil his utterances both public as well as in private were too racist and too it was he was paranoid all that stuff made us knew that every facility available to the FBI

was going to be used and was in fact being used to discredit the movement and that wire taps and surveillance certainly events that happened in some instances with SNCC the coincidence of things emerging when nobody knew either was the result of an informer in the group who informed or there is both of direct intervention through wire tapping and other surveillance we talked about that constantly so that there were times when we spoke to one another from safe phones given what the nature of the information was and where we would be fine a safe phone give me the number I'll go to a safe phone and call you we did that any number of times certainly did it with Dr. King especially during the years of the trial and the whole issue of Bobby Kennedy and Stan Levinson and the need that they had for Dr. King to begin to purge our ranks and of communists quote unquote the

the full dimension of that reality did not become very clear to us until we had access to the information in the archives the freedom of information's act when you saw all of it and but what was what what what defied us was that the very people whom we saw as allies to our cause whom we felt were people of fundamentally goodwill to us were also involved in wire tapping and were the ones whom we had reason to trust certainly was certainly to think of the Kennedy's and Bobby Kennedy and people in the justice department and the civil rights division tapping us when we were in what we considered to be open concert with them there was nothing that we ever said or didn't say to Bobby Kennedy

that that that wasn't reflective of what we were saying in private Dr. King was very much on the table and he was up front I mean we didn't have major but we weren't trying to overthrow the government they were no reasons for us to break up into cells we weren't consorting with the enemy whoever that would have been what the Soviet Union our generosity to our own cause was also that generosity that opened us up to anybody who would hear us and they could hear it all in an open forum the need to wire tap and to do what they did only serve later on to to be used as instruments to discredit by getting into our personal lives and getting into personal information which had nothing to do with politics uh moving to Dr. King in 1967-68 the war is escalating and the morality for the immorality of the war is now increasingly clear being urged I think but

stably in the kits of snake do we do remember him in that beginnings of that that quandary and then the moment when he decides to make the Riverside speech when he comes out and the reaction it was being urged not only by Dr. Carmichael and the kids of snake it was also being urged by the peace movement which was fairly large the peace movement was looking for a central place in which to be able to bring its energies and to have it uh propagandized and to have it understood uh Dr. King became the catalyst for all of it I just wanted to broaden the base certainly slick was very active in in moving that campaign along Dr. King had no problems with the issue morally or ethically that time in the very beginning was clearly understood what bothered him was the fact that in shopping the information around for feedback he found so many black people for instance who got

all of a sudden caught up in this wave of concerned about the definition between between black legitimate black aspiration for freedom in this country and the question about our patriotism that was a big that was a very difficult hurdle because the one thing that many people in the movement wanted to do honestly many many many of the black those who represented the black leadership from NAACP Royal Wilkins all the rest that ill you know wanted to know how the name of God could we be

making these demands on the federal government in the assistance of the black cause domestically and violate to this government by raising the issue that clearly had to do with foreign policy the the question raised by the black leadership of that period Royal Wilkins the NAACP and others the only one who was exempt from this was Afulap Randolph you know their position was how the name of God can you be asking the federal government to give us all the resources we require to change the domestic situation here at home and at the same time violate their their foreign policy

put them to the mat on an issue that is at the nerve center the very heart of this country at best we're going to be viewed as unpatriotic and having seized to hurt the country in its most a vulnerable moment he's in at worst what you're going to do is to have such a backlash from people that blacks will be further back than they'd ever been before it was a persuasive argument in terms of its potential but Dr. King had come to accept the fact that from a moral position and an ethical position the war was inhuman and unacceptable but also from a tactical position since the war was clearly illegal unconstitutional all the things that we've come to know that war

to be how were the blacks of this country ever going to be able to have the resources to do what had to be done if in fact integration was to come about if the government was spinning off all of these funds and monies into these illegal activities and the fact that blacks were the first to be drafted and when numerically the largest number serving in Vietnam and dying in large and numbers per capita than anyone else that the whole thing in its entirety was a campaign the Dr. King was prepared to go through with with the understanding that the true patriot the real American the one who was doing the country the greatest service was the one who would in fact state his case that it was illegal, immoral, unacceptable and not to the best interest of the country domestically as well as in its foreign policy.

This subject is just never to be discussed. More personal if you could if you were the night before the Riverside speech or the day after our kid some personal response to the rally, keep the personal response to the press. Do we get for close enough? Yes, I'm close. Dr. King had no problem with any of that he he clearly saw not only that the war was immoral, unethical, unconstitutional, illegal he also saw that since blacks were paying the price

they were paying the first to be drafted the most to be drafted the most on the front line numerically speaking comparatively per capita we were paying the biggest price for the war and all these resources being drained away he his mission was very clear to him the what he had to do and should do. For the rest of us I had no problems with it I really didn't have any problem from the beginning. I was already a peace activist I'd already come through certain periods of history in this country from the Second World War and then into the immediate period after the war Isaac Woodard and the blacks who were being murdered and and and named coming back as returning heroes from the Second World War then going through the McCarthy period and having the FBI on my case then and black listing you know all that kind of so by the time I got to Dr. King I had I was somewhat seasoned

to much of this already so in a way because of this background because of this history as along with others Dr. King was able to find important areas to to air his his his his his feelings where he found people who were sensitive to what he had to say and supportive of it after the speech of Riverside there was there was a lot of haggling before that by many who didn't want him to do it obviously those who wanted him to do it on the moral persuasive factors were far more pull out a pull out a little bit far more that was a false stick

what is the treaty this is take 11 market face um clearly that group was was was was more persuasive that position was more I think the first that I heard at the Riverside speech of anything that really and truly disturbed Dr. King were two articles that came out in the editorial of the New York Times in the Washington Post both newspapers were scathing in the adenunciation of Dr. King the Washington Post in particular was really quite aggressive in its language and it it sought to discredit Dr. King on every level it didn't take issue with him just on the war

it called him I'm trying to recall the article but it but it said as much this incompetent leader you know has now gone further in his incompetence that kind of language and the New York Times was not too far behind in the way it framed its denunciation of Dr. King on this issue so much so that later on when other publications came out also taking Dr. King to the to the mat Dr. King was not so much concerned about what those articles said about him personally as it was what they would do to the mood of the movement that this was not just a criticism as to a point of view on the war it now sought to discredit him in very profound ways leaving nothing intact that suggested the movement was

was the correct thing to to be happening in other words if you don't agree with me on the issue of Vietnam why kill the civil rights movement and all of those issues have been raised so there's a dimension that you don't agree with but when he saw it connected to the movement itself and all that was coming and appeared to be somewhat prophetic from the point of view of Roy Wilkins and others he was quite vulnerable to that and I'll never forget at a meeting Stan was there and everyone I said to him I said what fascinates me is you are you are deeply rooted and in the Bible you're deeply rooted in the Christian and the Christian theology it is the essence of much that you use to define where you go

how do you see yourself out of step with Jesus if you expect your utterances to be approved of by those who are the directors of vested interests in all that goes on in the world there's a whole misappropriation here I don't mind you're being upset and I don't mind you're waiting to take on the adversaries but you can't be wilted by this kind of language because you why do you have expectations of the Washington Post or the New York Times who clearly have a role in all of this that is when exercised in many ways is not to the best interest of poor people anywhere I mean they are the moneyed class they are the people who who stand to gain much from our failure or our successes and we'll play the game according to those interests and that kind of approach

to him in resolving his pain with this stuff worked he began to call upon his own resources to define what was going on and not see himself isolated or personal or so himself connected to host of people who've ever taken that kind of position in history leading movements who pay that price it was a meeting right around the area after the Riverside speech you had a session in your home I think with Stokeley people sometimes they conduct a king and they apparently they came to some kind of agreement that they were going to be and we're going to publicly criticise when and then they were not publicly criticised yes one of the things that I think everybody became very sensitive to we're out there no in the meeting with Stokeley and others at my home with that the king

it was one of several meetings but this one was most fruitful in the fact that we had come to a moment now when whatever differences existed would certainly have to be given the nature of where everybody was headed would certainly have to be viewed more carefully and every effort had to be made in order to hold discussions that would never make any disagreement become a matter of public policy or become a matter of public concern we were too vulnerable the issue of the war the issue of the movement itself civil rights the issue of the poor people's campaign all of America was up for grabs because by this time although all of these black institutions were beginning to play even more powerful roles than they had in the beginning one has to also

look at the fact that the white movement in this country the women's movement the labor movement the peace movement all of those movements were now beginning to find a new day for their own objectives they were beginning to find courage and platform and reason and spokespeople for their cause so that this country was in a huge mobilization on all levels including environmentalists and not the least of which so that the opportunity to bring coalitions together to make people come together and maybe at the end of all of this we can iron out differences and treat this thing as is often done there was a tremendous energy being put forth and it was at that meeting right after this that Snick and Dr. King and SCLC had agreed that there would be a moratorium on differences and if they became so crucial that there would be a conscious effort coming together

to discuss these things before they would erupt I was in my home and it was it was it was unacceptable although I had often discussed death with Dr. King so matter of fact one time on NBC when I hosted the tonight show Dr. King was one of the guests I hosted it for a week and it was quite a week Bobby Kennedy Dr. King and a lot of political and then it was Dr. King was he had come late to the show and he said uh he said I'd like it if it give me for being late we were on the air he said I'd like it if it give me for being late said because uh but uh my plane was late and I got to the airport and the driver was trying to get

here on time and he was cutting some corners and beating some lights that uh that made me say to him look young man I'd rather be Dr. Martin Luther King late than be the late Dr. Martin Luther King could you just drive a little bit let's be late it was with that handle that I then said to Dr. King death is very much in your arena death is very present in your life it is very present in the lives of anyone who is a follower of yours in all the campaigns how do you how do you come to grips with it and uh he went on to uh give a full explanation as to his view of death and this was particularly revealing on the show because it only gave him a chance to speak to the issues of his family but Dr. King had a a psychological problem and that he had a tick and he would get this tick

and it would come upon him and he would suffer with it for a given period of time I mean in a matter of minutes and it was quite difficult and uh we had noticed it and talked about it and it was obviously psychological and then after a while we discovered that this wasn't there anymore and I had said that Dr. King what happened and he said I've come to grips with the death I've come to grips with that and it was in that context that we then talked about it he'd come to grips with it because he believed that he could not clearly make decisions that had to be made in what to do if a preemptor was a concern for life in its in it in under any condition death in other words that uh he had to put in place not only the possibility of his own death but the death of his wife

the death of his children the death of those who were his followers the death of those who maybe in a march at any moment and he had to deal with this responsibility and uh I think that when he went and said you know I've been on the mountaintop I don't know that he was alluding to anything terribly specific although he could have been I think he was alluding to a host of conclusions and decisions that he had arrived at because he saw a new day in where he was going and where the movement was going and what had to be done I think that's what he saw on the mountaintop how did you feel on the day that you found out? the first thing that hit me with with his death was disbelief then swiftly pulling up on mechanisms that put that into reality because the first report was that he was just that he was shot and then not too long after that word came that he

was dead my wife and I were there and we you know the tears came and welled up but there was not much time for that part of it I got on the phone immediately after the first thing that he had just been shot and do what I always did was to call Kareta and the children first off to make to identify where they were whether he was incarcerated in prison or in this instance like this my I always call the family to just make sure that I knew where they were and what conditions they were in and what was what would be needed was Kareta in in Arkansas was she in California was she with the kids we were the kids so that because Dr. King one of the things that was done to give in peace of mind was for him to know that his his family would never be left without a lot of attention and care so that I love the job love all the aggression just clap and sticks and make

him noise the giving into the loss of Dr. King erupted but only in moments the real sense of grieving about him did not come for for me and I think from my wife and for a lot of others until later the act and the nature of the violence of it put everything in such jeopardy because of the grief that a lot of us immediately turned our attention to do not let this moment destroy everything that we have worked for because

anger which was obviously quite justified would have to be directed towards immediate objectives and towards goals that we have things that we could achieve as a collective rather than being left unattended because it would then do what in some places started to evidence itself in Washington and then what's another place when when the country was going up in flames so that when I flew immediately to Atlanta not only was there a lot that had to be done in terms of there was just an invasion of people and faces and things that we never heard from never knew before all kinds of people many of whom you've been trying to reach to help give us access to our to to to to the success of our cause all of a sudden came to the fore almost as if it was a photo opportunity in a way I don't mean to discredit many who came for out of real

genuine will but they were those who saw it at a time that that that that that it could be manipulated so we had to do what we could do to sort out those whom we're going to be the manipulators those who had to be put in place immediately to help move on with the poor people's campaign in a host of other issues and for a personal private conversation that I had with Carrera King to talk with her about going to Memphis to being there to picking up with the garbage workers and to carry on the campaign in just a matter of two days later two or three days and the discussion that we had with the family about the appropriateness of that everybody agreed there was so I had to I ran for a plane and all kinds of things to give Carrera mobility and to give other members to be so that people would in the midst of the grief still be committed to the movement and to see that the fallen Dr. King did not leave behind a movement that

that was going to be abandoned through all these disciples all these people who had been in place Josea Williams and the young JC Jackson Stoney Cooks where do you want me to go with that? Just with let's go back to the people of SCLC after this what happened? I would submit that that had Dr. King been given maybe another three years

let us assume that Destiny who said you're going to die if we had chosen a time three years later the movement would have been in an entirely different place than where it found itself at the time he was assassinated I think that Dr. King in the poor people's campaign with the garbage workers in Memphis was on a thrust here that was going to give a new and a much broader meaning to the movement which would have required a more broad-based use of people and a more broad-based input from leaders on a lot of levels so that the emerging group that inherited SCLC and other movements and other organizations were caught in a transitional period for which they were ill-equipped to do the task yes there was still the civil rights issues to be clarified there

was still the civil rights bill to be passed all that was fairly evident we had to take the move then however since it had been clearly around the issues of segregation integration and civil rights we're to carry it now to its next logical and more more dimensional place and as an interventional level had not yet all been put in place we're just in the process of doing that had Dr. King had three more years of refining the leaders and the people who came to being from all these diverse areas the movement would have been and the country would have been qualitatively different than where it found itself did you have a color resurrection city yes I went in going to resurrection city and looking at all the tents and all the people what I saw there more than anything else was a sea of hope and an assumption that we would arrive at the same places with the poor people's campaign that we had arrived at with the civil rights movement the one thing nobody

really understood clearly was that it wasn't going to happen because it only was there no real plan there was no leadership for it so that SCLC by the time Abernathy took over by the time it started to regroup by the time it started to took to call meetings together to do things there was no clarity there was no clarity as to what were the objectives anymore we knew the titles nobody had this specificity nobody knew the exact way in which to go about doing any of it that caused a lot of confusion and in the confusion a lot of people began to create their own little power pockets and began to seek to do their own thing I don't think I would not discredit my my comrades and my colleagues in this endeavor by saying it was a quest for power I think a lot

of people broke off and did things because they really believed that in in in in in light of no real understanding and no great leadership for this they would do what they could do in their own little environment that set up a lot of little camps it set up a Chicago camp it set up a Atlanta camp it set up a Memphis camp it set up a New York camp it set up and it was very difficult to get people to come together in a like-minded way that's a good place to move to Gary and Gary is one of those moments for us so the unity in a time of diversity is conflict and I can you give any sense of how diverse the elements were that people tried to get through like Gary was such a shiny moment in a way well what I thought about Gary at that meeting called by Richard Hatcher was that for the first time in one place under one roof almost every representation that the movement had was gathered together at this convention and it was an

enormously exciting experiment and an idea could we come together this diverse group and in the absence of the glue that held it together previously meaning Dr. King meaning Malcolm X in the absence of those leaders and particularly Dr. King what would he merge out of this could there be a consensus could there be a a conclusion arrived at that that would give uniformity and give a sense of purpose and that was not achieved in what way I mean I spoke with the Mama Baraka as a matter of fact it was at that time that something had happened with the Mama Baraka that really threw me for a loop although we had had some adversarial encounters earlier on in the movement and having been defined by him as a lost soul in this maze of freedom activity and liberation

activity in Gary he was very warm and very friendly which I accepted willingly as a spirit of of a new day but coupled with that when he told me he was now a Marxist and had found a new level of political philosophy and for doings I was kind of thrown for I didn't know quite how to handle that information I didn't know where it came from I didn't know that he'd had any such inclinations and the fact that it made itself evident at that place I could only begin to query what would his objectives be in his goal in America armed with this new philosophical position. Yes I think there was a lot of that I think that people were deeply concerned as to whether or not this moment would lead us into greater diversification or into greater controversy and into

greater alienation would it be confrontational that it wasn't there were hard things debated there's a lot going on I remember talking with Richard Hatcher at the convention and because he had put a lot into making this thing come about as a matter of fact it was setting up Gary Indiana to become a center for ongoing civil rights activity it hoped that in the city of Gary Indiana they'd be able to build a institution that would house become the major think tank of all people involved in the human rights and in the civil rights movement and as a matter of fact it's now being turned into a museum some of what has been achieved but this was the beginning of that moment that we would find

this place we'd come to this convening and I had never seen a collection of greater diversification except at the March on Washington at this meeting in Gary Indiana there was everyone represented the NAACP black Republicans black communists black Democrats all the civil rights organizations and individuals and there was a spirit of hope but there was also a sense that somewhere in this complex of bodies people are also looking to see in this squash of people in this overview if you could look into which one was going to be the leader which one or which

group was going to be the force people were looking for answers people looking for all kinds of things it was it was a very interesting convention um do you remember Jesse's nation time speech to be there in the birth of the baby in the water the other world water is broken birth of the baby nation time Jesse was also on his own campaign I think Jesse with push with his base in Chicago having come out of the late travels with Dr. King and having been at Memphis and all the controversy around that but he came out of this meeting as a I think was the first time that people heard Jesse in a way that we were to have heard that we were to hear Jesse from that moment on very articulate had a way with words most people described it as as his audition for air apparent to Dr. King's role I think Jesse has always worn that mantle I think he's always

felt that calling I don't think he felt the calling to be specifically Dr. King I think he's he knows that no one will ever be that but if anyone is to inherit Dr. King's legacy and move it forward to some campaign Jesse certainly has filled that role and started to play it even then even if even if objectives were not arrived at that everyone at hope would be achieved declarations of purpose I think with all that we had hope would be achieved and would come out of that meeting and I think there was some sense of reality that the greatest achievements would not

occur then what we were most hopeful of was that these conventions would continue and that even if on the first encounter we didn't come to real and important conclusions that we would have an ongoing dialogue with this format and out of it would emerge good thinking what I loved about was the pluralism of it what I loved about it was the diversity of it what I loved about it was the fact that it brought together people who were who had to put their stuff on the table and it had to be chewed over thoroughly and out of that I think I felt that if we were to be really healthy in terms of what would emerge that that was the best environment for to emerge because everybody had a chance to make input no one was left out and that's still to be done incidentally I remember the incident I don't remember the specifics of it what was it about okay the camera's

orange yeah I remember something like that yeah but it was the diversity it's very well in the October 27th there was a series of SCLC concerts around the country with Baez and Sammy Davis Jr. and you and they used to know Chicago and apparently the public response now because of the war and the other things wasn't what the other ones had been and the death of King was upset about that it was certainly a major force for Dr. King were celebrities the arts and he found in us as a community the ability to articulate into attract people to issues that was in some ways even more powerful in the press people reveal you know they view their artists and their choice with tremendous passion that's why people can get

very upset when we do anything they don't like and they can become very euphoric when we are doing things that they like we have a very special place I think in in the psyche of people and how they view us and Dr. King knew that that was an important source and one of my tasks was to continue to continuously corral that energy to reach out to my colleagues and to find the ones that were most vulnerable and willing and open to the information and find out those were most strategic and find out why they weren't vulnerable and the whole dialogues and whatnot and that was a constant and it began to give us tremendous relief not only in the PRing of our mission but also in the ability to raise funds after the Vietnam thing and when we went out and started to do concerts and started to or continued to do concerts there was a decided fall off and we were able to get back some even up up to the time of Montgomery and then we were always on the

downside but there was a period when for instance when we went to Houston it was the first place where we had been met by an act of calculated disruption a tear gas pellet was thrown into the air conditioning unit which fed into the auditorium that just panicked a lot of people in the concert was disrupted and there was a campaign in a lot of places where we went by white John Burgers and people who held up signs maintained that we were on patriotic and on American and and other devices and I'm not quite sure that the FBI and a lot of their people were not also playing a part in this in this kind of instigation of a and disruption after Dr. King's death the arts community continued to respond especially in the immediate days except at a large convening was held in Atlanta before the funeral in order to determine

what we would do in the celebration of Dr. King's death where we're going to take over the stadium would there be a concert would there be a night watch we felt we wanted to do that and the arts community was the best one to bring that off because first of all media would be sure to be there and we could then turn over the platform to those who articulate the hope of the future and to be able to give a one-voice view to the world on what we thought about Dr. King so that we would so that people would not be lost for information and even in that environment many among us came to it was a dissension and views it took place so we never pulled it off but we were able to do other concerts a big one with Cosby and Bob Streisand and other people of the Hollywood Bowl in LA and a few other places to maintain the momentum of the movement in the immediate days after Dr. King's murder.

It was evident there me here you had Maraca, a public part, you were there, was that a sense that people have a sense that they were doing something unusual? No, I think those of us who came out of a tradition of art in politics because I came out of the thirties and my father was a was a was a was a semen unemployed and he was organized for the maritime union, we did concerts all the time, the woody gothries of the world, the folk singers of the world, the folk songs of the period, a lot of writing in that period was writing about social and political issues, Steinbeck and Hemingway and Langston Hughes and James Weldon-Johnson's so that there was not a sense that we were unusual and I'm not too sure when we go to these events incidentally unless you're performing or unless you're specifically writing a poem that we're

there as artists, we're there as human beings who are doing something that belongs to the family and when we leave that environment we then begin to translate it into our songs and into our poetry and into our plays. Sometimes at these events we're required to do that because we sing at them, we'll bring political, you know, we bring a fabric to rallies by singing songs and you know I mean all what's a rally without a song it's a failure so that our mix in that was for some of us quite traditional it was for others quite unique I mean people who felt that art and politics never the twain meet well first of all those people are to me a great query I don't understand how they can pursue art and in its highest sense and not have a social and a human consciousness and be somehow involved in the affairs of the family of human beings it's impossible I mean for me all great art does that it's the only art that's that's meaningful and tangible. It's a way to Muhammad Ali

physical art but maybe you have thoughts of him when he was beginning to panic. I've often felt when people asked me about Muhammad Ali I said he was the genuine product of the moment he was the best example he was the the Negro kid who came up in the black moment who was cashiest clay that then became Muhammad Ali that took on all of the characteristics and was the embodiment of the thrust of the movement he was courageous he put his class issues on the line he didn't care about money he didn't care about the white man's success and the things that you aspire to he brought he brought America to its to its most wonderful and its most naked moment I will not play your game I will not kill in your behalf you are immoral unjust and I stand here to to test to not do with me what you will and he was terribly terribly powerful and and delicious and he he made him he made it he did it and was very inspirational I mean he was in many ways more inspiring than Dr. King more

inspiring than Malcolm more inspiring than those of course those people were the classic leaders here can this young kid right out of the heart of what it was we all said we were doing that was the that was the future that was the present that was the vitality of what we hope would emerge and for him to come here's the embodiment of all of it the perfect machine the great artist the incredible athlete the the the the the facel articulate sharp mind on issues the great sense of humor which was traditional to us anyway and his ability to stand courageously and say I put everything on the line for what I believe in and uh the giggo when I know I just had it over here is that a cut it was that that's a cut oh yeah we're almost right probably we can roll that you're going to know this takes seven to one okay let's uh mark the please

uh sometimes during these years you walked into the White House uh you would be invited there or you would be invited into presidential or uh people responsible for the country now you mean or then then yeah did you ever have an incident or a memory or something where you you tried to tell people the urgency what you felt uh when you were having your head access to power because before you were forbidden do you remember any events most of my visits to the White House and certainly my visits to the Justice Department on the body Kennedy or more often in that vein or more often to the objectives of trying to get them to focus on where we were going and what we were doing and what we were aspiring to and to try to find the the commonality what was good for the government and for the politics and for what they had to do and how they

had to do it mixed in with what the movement was demanding and had to do and where it had to go and how do you make how do you make it fit how do you make everybody come off successfully in it obviously that man compromise in a lot of ways the the government had to compromise the Kennedy certainly had to find moments of compromise and so did the movement one time in particular was because of the FBI and because of the great distrust justifiable that we all had of government and what they were doing was the concern about the draft and was particularly sensitive for SNCC because throughout the south where many of the people in SNCC held residence they were concerned about the fact that they would become draftable very very immediately and that even if they qualified or didn't qualify they would be drafted as an instrument of removing leadership from the field and that this was at best hurtful to our cause and at worst it was a misuse of government power and sensing that this was taking place and was a great consideration on the part of certain

states and certain governors and certain the draft boards and certain years that were run by by racists I had to take to Bobby Kennedy this information to ask that there be an intervention so that the very thing which was important to the White House which was voter registration because how sensitive they had become to the fact that black boats were very key to the future of this country and certainly to the future of the Democratic Party from that moment on because the White Olegarchy had been seriously broken by the Kennedy victory the way to yield and to get rid of all those people who bottled up our committees by seniority was by getting the black vote it was very very crucial and terribly important to the Democratic Party and the excruciatingly important to the Kennedys so that in the name of this these leaders these young heroes that were

in there doing that job if they were co-opted by the draft and taken out and whatnot who would do this work and it was very sensitive position for Bobby Kennedy to be in first of all he couldn't intervene because how could you meddle in the draft and give a sense of preferential treatment it was clearly illegal and certainly from a political point of view it was a terribly sensitive place to be in there was a sense at the funeral Dr King's funeral that we were at a moment in history that was very very unique all those hundreds of thousands of people who came all the people who had to express their loss